The book Seeking the Sacred Raven is the chronicle of conservation efforts for the Hawaiian Crow (or ‘Alalā) over several decades. The tale culminates in failure: the extinction of the crow in the wild.

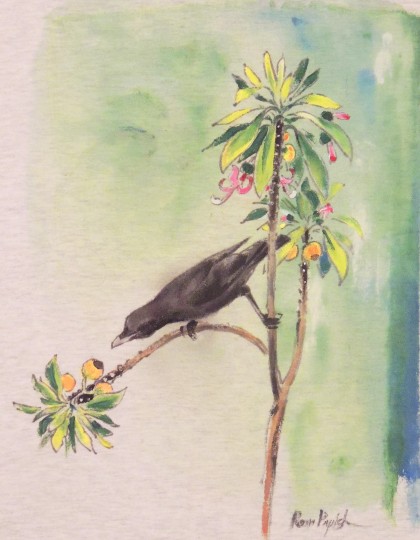

I was a bit player in this saga as a field assistant on the ‘Alalā project in the late 1990’s when I spent three months in the wet forest of south Kona on the slopes of Mauna Loa.

Since I was part of the project for such a short time, I was insulated from the human drama of the conservation effort.

This left me with the pure experience of getting to know the crows and their Hawaiian forest home.

My tasks were simple – keep tabs on the wild and released crows inhabiting a privately-owned ranch and trap the occasional offending mongoose.

The released birds wore radio tags, while the wild birds were easily found because they were territorial and noisy.

I would find the crows and spend time recording observations of them.

During songbird nesting season, they would switch to a steady diet of nestlings. It was exciting to watch. In my field notebook below, I call the nestlings “jumpers.”

The project was focused on raising birds in captivity and releasing them into the wild. Spirits were relatively high during my time there because there was a nice stock of young crows loose in the forest.

The release project was an emotional roller coaster for the full-timers because the young released birds were not surviving.

In fact, not long after I left the project there was a sweeping rash of deaths that ended the release program for good.

It was bad luck and biology.

The biologists were dedicated, passionate and competent with an elaborate process for easing the birds from captivity into the wild environment. But the unfortunate fact is that crows are complex, intelligent creatures that likely learn a great deal of their behaviors from older birds. They aren’t born knowing how to survive. They were babes in the woods.

The differences between the wild birds and released birds were obvious. The young birds had a limited repertoire of foraging behavior and vocalizations while the wild birds were breathtaking to watch and hear.

Many of the young birds were getting attacked and killed by the native Hawaiian hawk. Conservationists did everything they could given the context, but they couldn’t overcome the young crows’ need for parents.

All this is stressful enough, but as Seeking the Sacred Raven reports, the acrimony among parties involved in crow conservation made it all much worse.

The acrimony carried over even into reviews of the book. Scientists lashed out at the author’s bias in favor of the ranch owner whose land the crow occupied and against the conservationists.

Biases aside, the book gives a rare blow-by-blow account of a long and contentious conservation struggle. This case study likely has many parallels among other high-stakes conservation settings.

The take home for me is that simple human foibles can hobble conservation as much as any budget shortfall or unfavorable political climate.

We are human. We have egos to protect, we have difficulty keeping an open mind, we may not have entirely altruistic agendas, we are the hero of our own story.

And heroes need villains. Villains are the people with opinions that are different from our own, who believe they are just as right.

Would the crow be better off if everyone got along? It is difficult to say.

The danger for those of us who work in conservation is that our passion can bind pure love for nature with the toxicity that human foibles can sometimes generate.

I could see this in my superiors on the crow project. No one was having any fun even though they were “doing what they loved.”

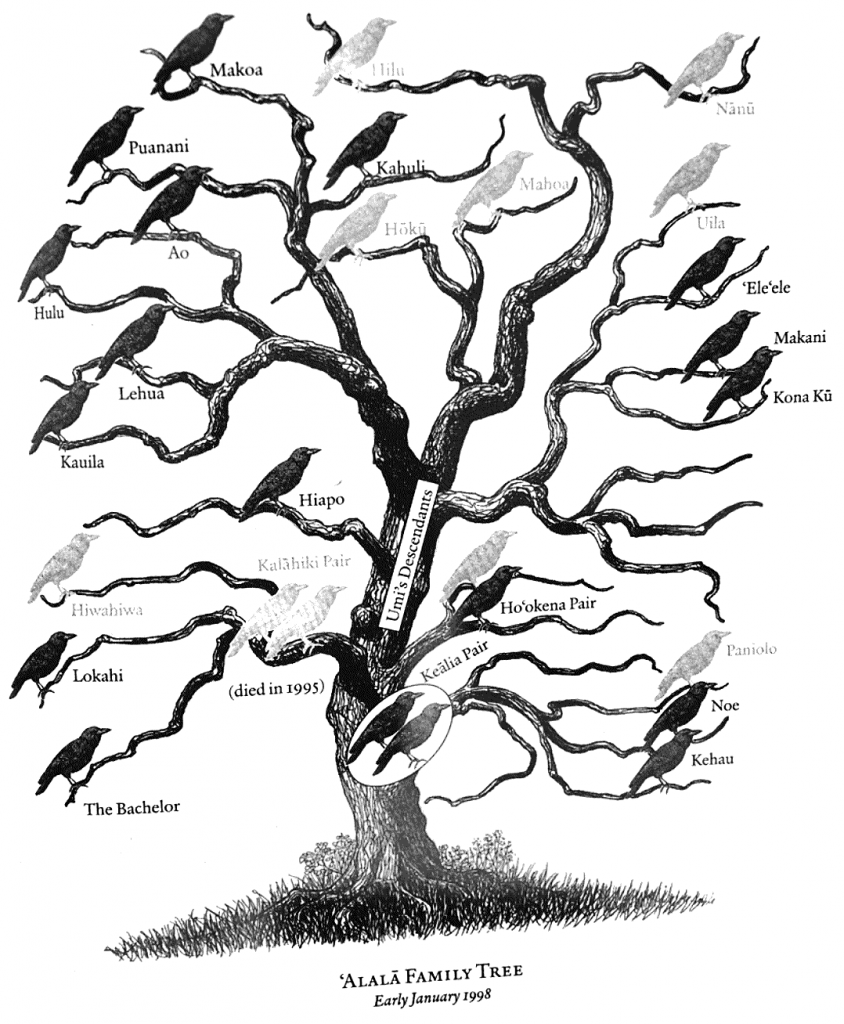

With the losses mounting, the few released birds left were brought back into captivity for their own safety in 1998 and 1999.

All that was left in the forest were the three last wild birds: the Kealia pair and the Ho’okena bird.

I had the honor of observing the Kealia pair’s nest from a blind while I was on the project. They were geriatric and laying infertile eggs, but kept at it year after year.

Their last try was 4 years after I left in 2002. Shortly after that they and their species disappeared in the wild. The videos in this post are of the Kealia pair at their last nest.