We New Jerseyans have it rough.

Although we have some of the most spectacular and extensive natural landscapes in the Northeast, these natural wonders seem to be overshadowed by our unshakable (negative) reputation.

Polls show that Americans have generally negative views on only five states, and yes, New Jersey is one of them.

We are known for our corruption, pollution, dense population and for the apocalyptic skyline of the Jersey Turnpike (”an image of sheer horror, no doubt about it”).

Throughout my life, I’ve noticed nothing kills a bit of small talk quicker than if you say you are from New Jersey. That is, unless the person you are talking to is also from New Jersey.

The Sopranos and the Jersey Shore did nothing to improve our reputation.

Thank goodness we have Bruce Springsteen.

I won’t defend the cultural landscape of New Jersey (except to say you should listen to Nebraska!), but I do want to stick up for its natural landscape.

Even in this category, perhaps New Jersey’s most famous natural landscape is the Meadowlands. These tidal wetlands along the Hackensack and Passaic Rivers are notable mainly for a litany of environmental abuses that have occurred there since colonization.

But then we have the Pine Barrens, which may arguably tie with the Meadowlands as our most famous natural landscape.

Unlike the Meadowlands, the Pine Barrens remain in good ecological condition, with stringent protections designed to keep them that way.

We have John Mcphee to thank for this. His book The Pine Barrens celebrated the fascinating natural and cultural history of this vast forest, now within a reserve that spans more than a million acres across central and southern New Jersey.

Mcphee’s writing, and a bit of serendipity, are ultimately responsible for the Pinelands Protection Act, which was passed in 1979.

The governor at the time, Brendan Byrne, just happened to be friends (and tennis partner) with Mcphee where they both lived in Princeton, New Jersey. During a gathering years later to celebrate the Pinelands Protection Act, Byrne said “certainly if I had not read The Pine Barrens, I would not have had the kind of interest in the Pinelands that I developed”.

Byrne also noted that until he took an interest in them, the Pinelands were on “nobody’s particular political agenda”. He said that the Act was his proudest achievement and noted that it was the only issue in state government that he responded to emotionally.

The Pine Barrens are not only impressive by New Jersey standards. They are the most extensive tract of Pine Barrens in the entire northeast and one of the most extensive tracts of forest in the eastern U.S. period.

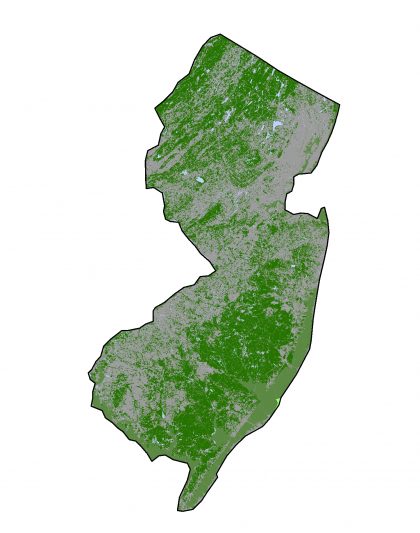

The map below depicts pine barrens landcover for all the Northeastern States. There are respectable tracts of this forest type in New York and Massachusetts, but the majority of it is in New Jersey.

Even less heralded than the Pine Barrens are New Jersey’s vast salt marshes. We have unbroken expanses of salt marshes in both the Delaware Bay and along the Atlantic Coast between the barrier islands and the mainland.

Here again, New Jersey rivals any state in the Northeast for tidal marsh acreage and holds its own against Virginia and Maryland in the Mid-Atlantic.

Our marshes really stand out when you consider their condition. Salt marshes are both threatened by sea level rise and are degraded by an array of human impacts.

Impoundment for farming, ditching and actions that affect tidal range all can contribute to the degradation of marshes.

For example in the Delaware Bay, more that half of the marshes there were impounded and farmed. This former activity has resulted in present-day marshes that are lower in elevation than they should be. The elevation loss has resulted in the loss of thousands of acres of marsh, with the remainder struggling to keep pace with sea level rise while attempting to also recover from farming-related elevation deficits.

While marsh farming was somewhat limited in extent, one author estimates that approximately 90% of all salt marshes in the Northeast have been ditched. Ditching for (ineffective) mosquito control became widespread in the early 20th century. It permanently changed the ecological character of marshes and we are still grappling to understand its effect on marshes’ capacity to keep pace with sea level rise.

More subtle have been changes in tidal range that result from channel deepening and shoreline hardening. The well-documented deterioration of marshes in Jamaica Bay, New York is the result of dramatic increases in tidal range. Due to a variety of human actions, the surface of the bay has decreased by more than 50% while the volume of the bay has increased by 350%.

The tidal range has increased by 1.3 feet causing rapid loss of marshes that formed under a completely different tidal regime.

(Red is marsh that has disappeared since 1951)

A SALT MARSH WILDERNESS

So why do New Jersey marshes stand out? Despite the environmental abuse of the Meadowlands, marsh farming in the Delaware Bay and widespread ditching, a big chunk of our marshes remain unscathed.

We are blessed to have tens of thousands of acres of Atlantic Coast marsh that are in a natural state, never ditched, diked or subjected to dramatic tidal alterations.

These wild marshes stretch from Cape May to Little Egg Harbor. The region is doubly blessed because it has a moderate tidal range. Research evidence is building that marshes with moderate to high tidal range are faring the best in the face of ongoing and future sea level rise.

Because of these double blessings, our untouched marshes may ultimately stand out as among the most resilient to sea level rise of our all our marshes.

North of Little Egg Harbor, things aren’t so rosy.

Almost all of the marsh subject to a first iteration of early 20th century ditching and a late 20th/early 21st century dose of Open Marsh Water Management, which carves small ponds amidst the grid of ditches.

The impact of these practices on a marshes’ capacity to respond to sea level rise is not well-understood.

In areas with complete alteration from ditching and Open Marsh Water Management, such as Barnegat Bay, it is very difficult to disentangle the effects of direct marsh alteration and sea level rise simply because there are no untouched marshes to serve as experimental “controls”.

On top of these alterations, much of central and north Jersey’s marshes have a very limited tidal range.

IN CONCLUSION

All this is to say we have alot to be proud of in New Jersey. I hope that with more pride, maybe we won’t take what we have for granted.

This means, for example, making sure the Pine Barrens stay Piney.

Despite the regulatory protection that the forest enjoys, recent research has revealed that much of our pine barrens are becoming oak forest because of fire suppression, especially near development. Without fire, pine barrens cease to exist.

In the Barnegat Bay watershed, 60% of the upland forest area will convert from pine to oak under current management practices. We may be losing more pine barrens than Massachusetts or New York ever had.

The orange on this map shows areas that have converted from pines to oak.

For salt marshes, it means recognizing that we have one the last huge tracts of untouched salt marshes in the Northeast. And furthermore it means making sure that these untouched marshes stay that way, both for the ecosystem they sustain and for the incredible value they have for studying the response of marshes to sea level rise separate from their response to human impacts.

Somehow we need to stand up for our reputation as a place of singular natural wonders while acknowledging that we still a lot of work to do in rehabilitating New Jersey’s overall public image.

EPILOGUE

Jersey pride may also mean making sure that when the Sopranos go the the Pine Barrens, they really go to the Pine Barrens.

No wonder these guys got lost in the woods – they thought they were in the Pine Barrens, but they were actually in the New York piedmont (where filming occurred).

According to Wikipedia, the episode was originally intended to be filmed in New Jersey but a local politician denied their permit and called the Sopranos “a disgrace to Italians”. This same politician was later jailed for corruption.

Like I said, there’s still a lot of work to do.