You are looking at an aerial view of Cedar Swamp Creek, a tidal tributary of the Great Egg Harbor River in Cape May County, NJ. It is the closest thing to wilderness we can hope for in our densely-packed corner of the world.

Only one road crosses the swampy forests of this creek’s headwaters which span the whole Cape May Peninsula. At some point upstream these forests become another creek’s headwaters (Dennis Creek) and then drain westward into the Delaware Bay.

The creek itself and the Atlantic white cedar and red maple swamps above it are difficult to access and explore, with no marked trails and only obscure access points from the roads that skirt the wilderness.

But just about ninety years ago this tidal marsh basin was a very civilized place. Today it is a fine example of tidal brackish marsh, with a mix of spartina and narrow-leaf cattail.

No modern visitor would guess by looking at it that once this marsh, every bit of it, was farmland.

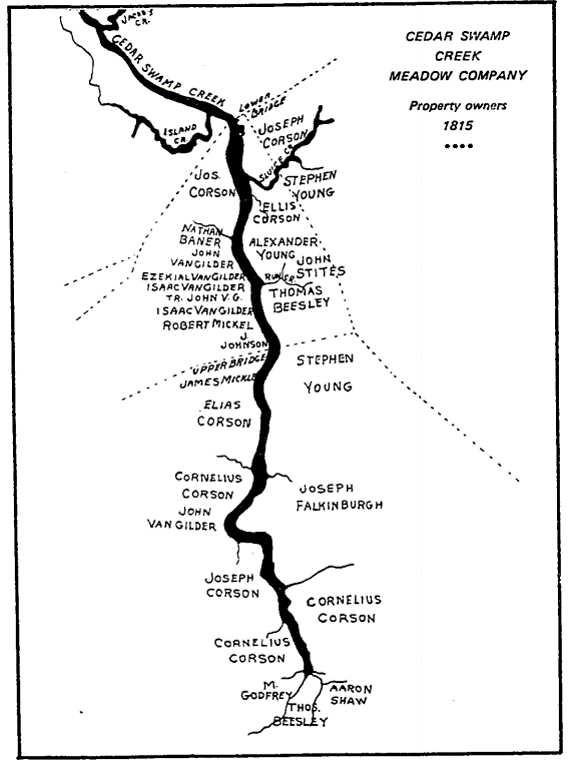

The black and white map shows land ownership across what is now tidal marsh. When the map was made, a dam at the lower end of the creek (lower bridge, which is at the top of the map) kept tidal waters back and allowed farmers to move in and grow crops.

I know this only because I came across an obscure 1977 publication that documents the history of the area.

This document reprinted the “Minutes of the Cedar Swamp Creek Meadow Company,” which recorded the meetings of a joint venture of the creek’s landowners that maintained the dam and other infrastructure.

Meadow Banking Companies were sanctioned by NJ law in 1815 to form these joint ventures to dike off tidal marshes throughout the state to so that these marshes could be “reclaimed” and used as farmland for either salt hay or upland crops, depending on the setting.

1815 is precisely the year when the Cedar Swamp Meadow Banking Company formed, and as the author of the history, Joyce Van Vorst, relays:

Indeed, as Van Vorst tells us, the dam eventually failed. The minutes of the meadow banking company are telling.

Most of their business, year after year, was devoted to maintaining the dam. It continually broke through under the strains of tides and storms. It is another example of how the diking of marshes makes a naturally resilient system a very brittle system, the opposite of resilient.

Wild tidal marshes brook storms like water off a duck’s back, but once dikes and dams are in place storms spell catastrophe.

Over the years the meadow company squabbled over who might do the repair work and who might pay for it. Decade upon decade of breaches led to a final dissolution of the venture in 1924, just past 100 years after it was formed.

The minutes are short on detail, but the ultimate decision was forced by the county government who feared for the integrity of the road that crossed over the dam. The county took control, breached the dam, and that was all she wrote.

For 90 years the marshes of the meadow company have gone their own way, recovering from 100+ years of being farms. It is likely that all those years of tidal restriction left the Cedar Swamp Creek marshes much lower in elevation than when they started.

This is because when marshes are dried out by tidal restrictions, the organic peat that is preserved by low oxygen conditions of saturated soil becomes oxygenated and decompose, causing a relatively sudden drop in surface elevation. Furthermore, the tides which were kept out would have supplied fresh suspended sediment to help the marshes build themselves vertically to keep up with sea level rise (and due to geologic phenomena, it was rising steadily even in colonial times).

If I imagine the scene in 1924, I see bald marshes: mudflats where there were farms. But the sudden rush of tides brought fresh suspended sediment in to help the marshes recover. And over the decades these marshes did their resilient best to recover.

Now the marshes are fully vegetated. But knowing the history, I am left wondering if they look anything like the marshes that were there before the farms. The truth is, these marshes are pretty low in elevation and unstable, very difficult to walk on (a quick way to assess marsh condition is “can you walk on it?”)

There’s no way to know what the pre-colonial marsh of this area looked like, but chances are that this marsh is lower relative to sea level than it should be. It is forced to come from behind, making up the deficit wrought by 100 years of farming while at the same time keeping up with accelerating sea level rise. It’s a similar story elsewhere, particularly on the Delaware Bay, where most of the marshes were diked at some point in the past.